Protect Your Heart with This Exercise Plan

Your cardiovascular system is built to support physical activity, and rewards you for it with a longer, healthier life.

Decades before Mike T. Nelson, Ph.D., earned those letters after his name, he was marked as someone who would never take his heart's health for granted. Literally marked.

"I had open heart surgery when I was four and a half," he says, thanks to a nearly fatal congenital defect. "I was in the hospital for 10 days, and I still have a pretty good-sized scar."

But it was his math skills, rather than the vertical stripe on his chest, that made him an expert in some of the more obscure areas of human metabolism and cardiac health. When he entered the doctoral program in exercise science at the University of Minnesota, the team studying heart-rate variability (HRV) needed someone to run the numbers, and Nelson was called into service.

Don't feel bad if you've never heard of HRV. Most of us assume that the heart, like everything else in the human body, is healthiest when it works with clocklike precision. Isn't that why we call it a ticker? Up until the mid-1960s, that's what doctors and exercise scientists believed, too.

We now know the opposite is true. Even at rest, the heart varies the time between beats. In fact, the steadiest rhythms are usually found in the unhealthiest hearts.

"Once you start to lose that variability, we know that's a marker for cardiac disease," Nelson says. HRV also declines in people with depression, PTSD, and asthma.

Which brings us to exercise. HRV is just one of many aspects of heart health affected by physical activity. Some, like improved cardiovascular fitness, are a direct result of a structured exercise program. Others, as you'll see, protect the heart indirectly-sometimes in ways even scientists like Nelson don't yet understand.

The Basics: How Exercise Helps Your Heart

Yes, exercise is good for your heart. You can't walk into or out of the doctor's office without a reminder that a little movement goes a long way. A lot of movement goes even farther.

We have mountains of research to back this up. For example, a recent study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society found that older men and women who do the most physical activity in their leisure time were 53 percent less likely to die of any cause, 66 percent less likely to die of cardiovascular disease, and 45 percent less likely to have a heart attack. Those in the “moderate” range of physical activity also had lower risks across the board, compared to the ones who moved the least.

From other research, we know that physical activity improves all the following aspects of cardiac health:

- Lowers blood pressure

- Improves cardiac function

- Improves cardiovascular fitness

- Lowers insulin resistance

- Lowers blood sugar

- Improves cholesterol levels

- Reduces inflammation

Then there are the indirect ways exercise supports the heart:

- It helps you maintain your current weight, which is really a two-for-one benefit: If you've lost weight, exercise helps you keep it off. It also helps you avoid gaining weight in the first place.

- It helps reduce body fat, especially the fat that hides in the muscles and organs of sedentary people and wreaks havoc on your metabolism.

- It helps maintain your functional abilities, allowing you to move without pain, get over and around obstacles, pick things up and put them down, play with your grandkids, or whatever else you consider part of your normal life.

Lower weight, less fat, and higher levels of functional ability all make physical activity easier, creating a virtuous loop: The more you exercise, the easier it is to continue exercising. And if you continue exercising, you’ll reap the benefits.

There's a pretty good chance you know much of this already. So let's go a little deeper.

The Details: What Matters Most and Why

When researchers use terms like "leisure time physical activity," they're talking about movement in general, like walking or hiking, riding a bike, dancing, gardening, or swimming. It's a separate category from structured exercise or sports.

The term "exercise" usually means endurance-type training, or what most of us would call aerobics or cardio. It shouldn't surprise anyone that a form of exercise called "cardio" would improve the health of your cardiovascular system.

"The heart is a muscle," Nelson says. "Exercising it makes it stronger."

Specifically, if you do it long enough and with enough effort, you'll see two massively important changes: Your heart will pump more blood with every beat, and you'll have a lower resting heart rate. Thus, your heart can do its job with less work. "You've increased the efficiency of the cardiovascular system," Nelson says.

That's the most direct way to protect your heart muscle. You can also protect it indirectly by making all your other muscles stronger.

A growing body of research shows that the strongest people have the lowest risk of dying from any cause, and in most studies, a lower risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. The link between strength and longevity holds up even when researchers factor in variables like cardiovascular fitness. Higher levels of strength somehow protect your heart.

How? Nobody really knows yet. A 2015 study in the European Journal of Internal Medicine offers a few potential explanations. It could be linked to strength training, which helps you maintain muscle mass as you get older. That muscle, in turn, sucks up excess glucose from your blood and generates hormones that help reduce inflammation.

Subscribe to our newsletter

It's quick and easy. You could be one of the 13 million people who are eligible.

Already a member? Click to discover our 15,000+ participating locations.

Follow Us

The simplest explanation is that a stronger body is almost always more functional, enabling you to move more and do more.

So now we get to the most important question: How much do you need to do to get all these benefits?

Your Action Plan: How to Hit the Sweet Spot

When it comes to everyday movement-walking, working in your yard, or running errands-we know that some is better than none, and a lot is better than some. There's probably a point of diminishing returns, but we can't really say what it is. As long as the movement is pain-free, it's hard to see a downside to doing as much as you want.

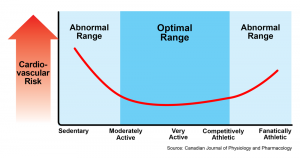

Structured exercise is different. Since the goal is to challenge yourself, your body needs time to recover between workouts. That's why some researchers believe there's a U-shaped curve for the benefits of exercise.

For example, in one 2014 study, the highest risk of cardiovascular disease is among those who are sedentary. The risk drops steeply as soon as you get off the couch, and keeps dropping until you get to the "very active" range. Those who are "competitively athletic"-training for and competing in marathons or triathlons, for example-start to see an uptick in heart problems. Then there's a big rise in cardiac risk for those who are "fanatically athletic."

With strength training, the guidelines are simpler. A 2016 study in Preventive Medicine shows that working out at least twice per week lowers your risk of cardiac death by 41 percent and the odds of dying from any cause by 45 percent.

All in all, these guidelines point in just one direction. "The more functional you are as a human being, the longer you're probably going to live," Nelson says. "If you get winded walking across the room, I wouldn't place a longevity bet on you."

Want to make sure you're doing everything you can to help your heart-and able to stay active as possible? Check with your doctor, and get moving.

Lou Schuler is an award-winning journalist and author and also a certified strength and conditioning specialist. His latest book is The Natural Way to Beat Diabetes, which he wrote with Dr. Spencer Nadolsky.